Are cats the sacred animals of Chiang Mai?

Unofficially, yes, and there are some unique benefits that flow into cities that embrace a more-than-human world.

Chiang Mai is a cat-filled city.

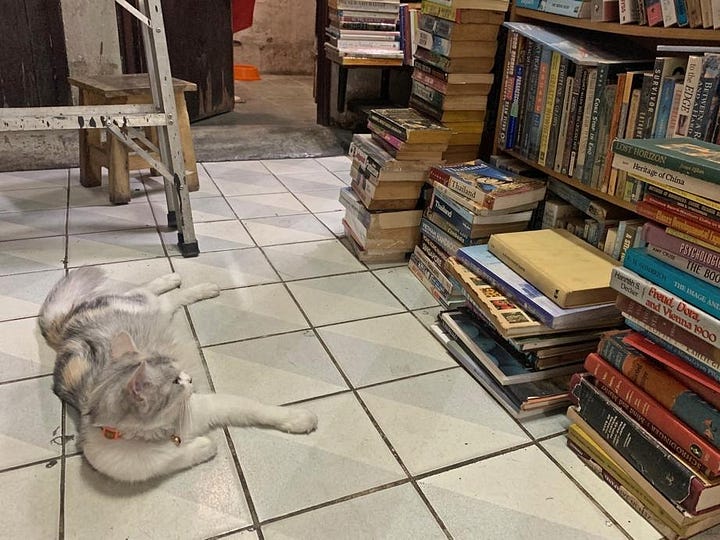

Hundreds, if not thousands, of them jump and strut and climb and nap all over the city like it’s a giant playground. Some are owned, others feral. Regardless, you’ll find both on roofs, in restaurants, near bookshelves, and on top of phone booths that have seen better days.

Some have fancy names—like Jeweled Cloth, Dark Sapphire, and Moon Diamond—while others have decidedly un-fancy names—like tabby. Regardless of pedigree, I prefer to name them by where I find them—hence, the Lazy Ledge Cat, the Witchy Bench Cats, the Screaming Roof Cat, and, of course, the Phone Booth Cat.

During an average morning walk the other day1 , I turned to my right to find Phone Booth Cat staring at me. Unexpected joy bristled through my body as a smile grew on my face. But, I kept it together, took out my phone and snapped a picture.2

Like the Cheshire Cat, the smile stayed as I walked away, and a question grew with it: why is there a cat atop a phone booth surrounded by trees in a city of 127,000 people?

The answer, in short, is that it’s there to teach us that the world’s not all about us. Before we can really appreciate that answer, however, we need to take a tour through Thai culture, the domestication of cats 12,000 years ago, and the development of human self awareness.

…

(Yes, there will be plenty more pictures of cats.)

Cats and Thailand: language, culture, and buddhism

Cats and Thai language

Thai people call cats “maew.”

When written in Thai script, “maew” is spelled “แมว.” The “ม” makes the “m” in “man” sound, the “ว” makes the “w” in “wing” sound, and the “แ” makes the “aa” in “air” sound.3

The word maew (แมว) sounds exactly like the sound cats makes when they want people’s attention. That sound is reserved exclusively for humans.4 This suggests it’s what they want to be called—their preferred (or pur-furred) pronoun if you will. Either by a stroke of luck, intuitive insight, or the influence of animism, Thais understood and decided to name cats after the sound they used exclusively to speak to humans.5

Cats and Thai Culture

Cats have been worshipped and tied to notions of luck for a very long time. The Tamra Maew, or “Treatises of Cats,” dates back hundreds of years and lists various types of auspicious cats. One of those auspicious cats was the Wichien Mass, or “Siamese cat.” (For those of you who haven’t been researching the history of Thailand to write cat articles, Thailand was called “Siam” until 1939.)6

Siamese cats were prized by royalty, given to foreign dignitaries, and were even part of the coronation of His Majesty King Maha Vajiralongkorn in 2019. According to the Iranian Embassy’s “The Real House Cats of Siam” (claps and kudos to whoever’s writing the headlines at the Iranian Embassy), it went like this:

“For the royal proceeding, a Wichien Maat carefully selected for its pure coat color was carried into the palace at an auspicious time and placed on a mattress. The appointed cat bearer then performed a prayer, bidding happiness and abundant fortune for the occupant of the residence.”

Another major part of the ceremony is upholding the “Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha.” Which brings us to Buddhism.

Cats and Thai Buddhism

Of Thailand’s 70 million people, about 64 million are Buddhist. They mostly follow Theravada Buddhism, which is the oldest existing school based on the earliest Buddhist teachings. Oddly enough, that tradition shares a surprising number of ideals with cats.

In philosopher (and cat-lover) John Gray’s Feline Ethics, he describes cats as embodying “selfless egoism.” They’re egotistical because they’re only concerned about themselves and those they love. They’re selfless because they have no self-image they want to maintain or improve upon.

Early Buddhists also aimed at a kind of selfless egoism. They wanted to “shed the illusion of the self in order to achieve a state of complete quietude or nirvana.” Rather than selfless acts of compassion, they wanted to liberate themselves from the illusion of self.

Only later on, as Gray writes, “did the idea arise that in a supreme act of selflessness an awakened individual (bodhisattva) might renounce nirvana to be reborn to liberate all sentient beings.”

A cat’s selflessness is inborn because they don’t develop a sense of self. Hence, they don’t need liberation from that self. Humans, on the other hand, have developed a sense of self. Most people are uncomfortable with theirs, so they try to change it. Theravada Buddhists try to get rid of it entirely. Cats reach that goal seemingly without effort, which makes them a good fit for a Buddhist country.

That being said, if they’re such a great fit, why not keep them inside where it’s safe?

The “domestication” of cats

Because cats aren’t domesticated.

Huh?

Sure, some cats may live in apartments or houses or even use forks to eat from time to time but that’s a far cry from the way dogs, cows, horses and other domesticated animals behave. Humans train dogs and cows to be useful to them. Cats seem to have trained humans to do the same for them.

It all started 12,000 years ago when cats and humans started living together. Cats made the first move. They walked up to farming communities in the Near East and started casually killing the rodents that were eating the stored grains people depended on.

“Ok. Well… you can stay,” the people said.

“Maew,” the cats replied.

The cats settled into their new homes, feasting off bits of meat left by humans alongside their standard fare of mice, rats, and other rodents. As small villages grew into cities that expanded across the globe, cats were put on ships to control pest. In short, they figured out a way to get free room and board while exploring the world.

Most likely, cats made it to Chiang Mai in 1296 when the city was founded. About 726 years later (aka 2023), they’re still here lounging on ledges, screaming on rooftops, and trying to figure out what book to read.

So, although cats have been “domesticated” in the sense of living in domestic environments, they were never entirely brought under human control.

Unlike dogs who sit on command or horses who gallop on cue, cats won’t do a goddam thing unless they want to. If it expresses their nature, they’ll do it—if they control pests, it’s to express their nature as hunters. If humans find that useful, it’s a happy coincidence. However, trying to get cats to hunt on cue is a fool’s errand. You can’t herd cats, as they say.

Part of the genius of Chiang Mai’s approach to cats is that they give them room to express their semi-domesticated nature, rather than trying to herd them into a neat little cue.

On multiple walks, I’ve seen Thai people engaged in seemingly earnest conversations cats outside convenience stores. They argue with them, scold them, share food with them, and generally treat them like equally sovereign creatures worthy of respect.

In giving cats space to roam, Chiang Mai gives humans a chance to embrace a more-than-human world.7

A more-than-human world

In the highly litigious US, city cats are more likely to get zoned out of existence than admired. In Chiang Mai, they’re given freedom and admiration in equal measure. Although imperfect, it’s refreshing. Stray cats pose a problem8, but cats in general provide an opportunity for humans to learn more—and expand beyond—themselves.

How?

Through “mirroring”.

In Coming to Our Senses, historian Morris Berman describes the importance of mirrors in the development of self-awareness. Upon birth, newborn babies experience the internal and external worlds as one—when they’re hungry, they assume the entire world is hungry as well. Although aware, they aren’t self-aware because the self hasn’t yet emerged as a separate “thing” in the world.

That takes about three years.

In that time, their internal-external unity breaks and the two worlds drift apart.

It starts with self-recognition. Infants recognize how they look—their body image—by having mum copy how they look and reflect it back to them. As Berman writes:

“The baby sees the mother’s face, and what her face portrays is related to what she sees in its face. Thus for the baby, the mother’s face acts as a mirror; she gives back to the baby its own self.”

Through this act of mirroring, infants learn to recognize themselves until, around 18 months into life, they pass the so-called mirror test. When placed in front of a mirror with a dot on their face, they will recognize themselves in the mirror and touch or wipe away the dot.

Elephants, apes, dolphins, whales, magpies, and a few others can also pass the test.

Cats…not so much.

That self-recognition grows into the complex notion of self-awareness by age three, which is about questioning and tweaking the image of the mirror to better understand what it is. Despite their differences, both self-recognition and self-awareness require mirroring for their development.

As we’ve seen above, “mirroring” doesn’t have to mean physical mirrors.9 Other people and animals can reflect images back to us as well. The way animals like cats regard us—playfully, skeptically, fearfully—affects how we regard ourselves.

Unfortunately, as Berman shows, when Europe rapidly industrialized in the 18th and 19th centuries, they removed animals from domestic and urban environments. Sure, it led to less horse dung in the hallways, but the tradeoff was the loss of a significant source of nonhuman feedback. This, in turn, promoted a far more human-centric world.

Just like celebrities surrounded by Yes Men falling into a pit of narcissism and delusion, the banishing of animals from city life wounded people on a deeply psychological level.

As John Gray writes:

“Humans need something other than the human world, or else they go mad. Animism — the oldest and most universal religion — met this need by recognizing non-human animals as our spiritual equals, even our superiors. Worshipping these other creatures, our ancestors were able to interact with a life beyond their own.”

Finding ways to live with animals in cities without micromanaging their every move expands our human-centric world at a time when a lack of non-human feedback is destroying it. Whether consciously or not, Chiang Mai seems to get that.

In a technocratic world hellbent on controlling everything, the fact that we can’t herd cats is a gentle reminder that not everything needs to be herded.10 Sometimes it’s better to just let cats do their thing. For some, that’s screaming on a rooftop, for others, it’s lazing on a concrete ledge, and for cats with an eye for old technology, it’s sitting atop abandoned telephone poles staring out at whoever passes by.

*It took quite a few walks, many hours of reading, and lots of thinking about cats to finish this post. If you learned, laughed, or found something extra in the ordinary, consider supporting my work. You can do that by sharing it with one person in real life, sharing it to multiple people online, subscribing to The Mundane Exotic for free, or buying me a coffee. *

In a country where the seasons are jokingly (but also totally seriously) broken into “hot” and “hotter,” morning is the best time to walk.

That last sentence would sound insane only 20 years ago, as the late-great comedian Norm Macdonald (RIP) pointed out.

In written Thai, vowels can go before, after, above, below, or surrounding consonants, they’re almost always pronounced after the consonants. Also, there’s 16 vowels, 44 consonants, no punctuation marks or (few if any) spaces between words. Learn more here :)

Sure, some kittens meow, but no self-respecting adult cat meows to other self-respecting adult cats.

English-speakers, on the other hand, settled on “cat”—a sound no cat has ever or will ever make.

This is also the origin of the term siamese twins.

A phrase popularized in David Abram’s excellent book, The Spell of the Sensuous.

My Australian editor tells me that'cats pose a serious danger to wildlife in certain places. Fair enough, but there could still be greater reverence and space sharing for other animals. It doesn’t have to always be cats. Kangaroos are cool too.

That being said, Berman found that, throughout history, times of high mirror use corresponded to times of high self-awareness and interiority, and vice versa. Those aren’t always good things; a useful reminder in the age of selfies.

Maybe the appeal of cats on the internet is that in a world of micromanagement, they will not be micromanaged. If they don’t want to do something, they won’t do it. If you kick them out of the house and refuse to let them back in, they’ll probably find another family, figure out something in the wild, or else be content to die — that kind of freedom is liberating.

Lovely piece, cats, Thai culture, Buddhism, developmental psychology, and- cats. And weaving the narrative between them. Glad I found this via The Books that Made Us Roundup

Really stellar stuff. Can't get enough.